Custom knifemaking!

Coulter's Smithing Home

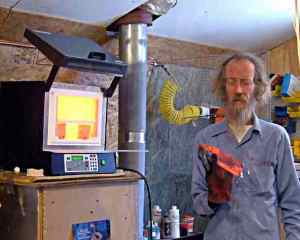

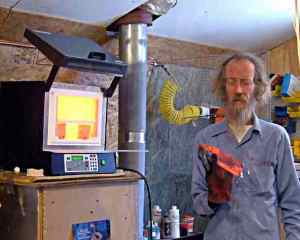

Air quenching a composite metal cleaver. Bet this

would go through butter!

We make custom knives here, sort of as a hobby, but it has turned out to

be a profitable one. We are not as good at it as some of the masters,

like, for example

this guy, or

this guy,

but so far we are not getting any complaints either. Unlike some

of the pros who are not really custom, but make batches and then

sell them, we actually make each knife for each customer, to a design

the customer helps with or likes -- this sometimes results in unusual

designs, which is fine with us – and more fun sometimes. We fit

each to the customer's hand,

something impossible to do in batches. We also pick the steel type

based on the customer's desires, uses, and skills with knife type tools.

We make custom knives here, sort of as a hobby, but it has turned out to

be a profitable one. We are not as good at it as some of the masters,

like, for example

this guy, or

this guy,

but so far we are not getting any complaints either. Unlike some

of the pros who are not really custom, but make batches and then

sell them, we actually make each knife for each customer, to a design

the customer helps with or likes -- this sometimes results in unusual

designs, which is fine with us – and more fun sometimes. We fit

each to the customer's hand,

something impossible to do in batches. We also pick the steel type

based on the customer's desires, uses, and skills with knife type tools.

Believe it or not, there are people who think nothing of using a

fine knife to cut radiator hose, or to pry on something. For one customer

we simply ground a screwdriver bit onto the end, because we knew this

person would use it that way anyway. Of course, he got a different

sort of steel than what we would use for a gourmet chef's blade!

So, to sum up our philosophy on all this, if it's worth doing, it's

worth doing right, and it can't be custom unless the customer has

quite a lot of input. We just can't give you the best unless we know

what is best for you. And that is emphatically not the same

thing for everyone! Naturally, one has to have fairly deep pockets

or be a really good friend to motivate people who normally make

really decent bucks programming to take a few days off and make a knife.

It seems there are such people around, who appreciate the finer

things that can't be had any other way, and who would rather use

an exquisite tool every day that lasts a lifetime rather than go through

a bunch of WalMart stainless steel knives that won't take or hold and edge,

don't fit the hand, and so on. We cater to those people.

Sadly, we only have a few pictures of knives we've made, but will add

more as we make more. The good ones go out the door! We didn't

think this would turn into a business, so we didn't document them all. Life

is funny that way, sometimes you try and fail, sometimes success

surprises you when you weren't really trying.

Ok, here's some good stuff we do have pictures of. These were Christmas

presents. In the left picture, the center cleaver has a Cedar handle, the left

and bottom ones are different samples of Cherry, and the prototype on top

is Walnut. These

cleavers use S7 for the blade, which is welded to regular 1020 steel for

the body parts, which saves quite a lot of money. We built a jig to do the

MIG welding in the milling machine so the welds come out perfect, and

can then be made flat without having to do any new setup.

These haven't had the gold plating layer added yet, or the final wood finish.

In the right picture there are some Tanto style blades, which make really

nice kitchen knives. Our first hand-forged knives were curved, and one

customer really didn't like that, so we tried another way after watching

how she used knives to do things like open packages. This is the result,

and it seems pretty popular. Handles are Walnut, brass, Oak, and Aluminum.

We cut threads on the aluminum one and hollowed it out for the recipient,

so he can use it as a ruler as well as a knife. The oak came from some

very old, probably over 100 years unfinished oak flooring found in a local

barn, and is "distressed". The customer asked for the

"crooked" blade. Keeps the knife from rolling around on

the counter, that's for sure!

Steels we use

Different strokes, as the saying goes. Here we use A2, O1, S7, and various

carbon steels, sometimes case-hardening those. We prefer the tool

steels, as they are a lot easier to heat treat without warping them. We have

not found any stainless alloy that works well enough to suit us, so we don't

use any stainless. We do, however, electroplate or blue the blades we

make for rust resistence, and in the case of nickel plate, to make them

slip through things better. We also engrave and inlay things like gold. A

heat treatment trick we know can leave the blade surface with a texture

sort of like a maze, and this looks very nice nickel and then gold plated,

with the gold plating taken off the high spots. It looks like someone

spent a good part of a lifetime engraving and inlaying, but is easy and

cheap to do. We can plate most metals on to knife steel, but we like

nickel for being slippery, cobalt for being very pretty, and gold for the same

reason. We can also anodize aluminum handle parts and put just

about any artwork you can think of on there.

Steel Properties from a knifemakers perspective.

| A2 |

Our all around favorite steel for those who will use a knife for cutting only.

Takes and holds a spooky-sharp edge. Really good for meat and veggies.

Best all around tradeoff for hardness vs brittleness we've used. |

| O1 |

This is what we like to use if we will blue the blade, as it takes the blueing

better. Will get almost as sharp as A2, and hold an edge almost as well. |

| S7 |

S7 is a very tough steel, but not all that hard as tool steels go.

It is the steel of choice if any prying or pounding is going to happen

to the blade. Good for cleavers especially. |

| 1075 and up |

Carbon steels are the traditional choice. They have a tendency to warp during

the quench in heat treating, though, which reduces the productive yield.

They can be made so hard that they become difficult to sharpen, but in that

state they are also pretty brittle, and drawing the temper to the point they lose

brittleness leaves them soft again. The tool steels have a better hardness/toughness

tradeoff. If relatively mild carbon steel is case hardened, it can be very good,

but then requires two heat treats to be done really right. So the cheap steel is

actually the most expensive. Shouldn't be a surprise. |

As you can see, selecting the right steel is very important to the end user. Some

folks want

really good sharp blades, and will use them as cutting tools only. We can specialty heat

treat for those folks so they get just what they want. We can also make a great knife to

kick around the bench or garage, but it would not be made anything like the same

way, or out of the same alloys. If you really want us to use some other alloy you think

might be best for you, we will, though it may cost more if yields are low or heat treat

is especially difficult.

One of our TODO projects is to make an induction hardener, which will improve all this

heat treating stuff a lot, as we can do it in a vacuum and have no scaling and no

warping. That oven uses considerable kWh for a solar system! We can do

TRUE Damascus steel as well, which is not what most of the knife business

calls by the same name. They mean any two or more steels forge welded and folded,

etched to show the nice pattern. What we mean by that word is real Wootz,

hard ferrite particles suspended in relatively mild steel. This is what those fantastic

swords were made of. It's good stuff, but hard (expensive) to make. Unless you

want it for historical reasons, the tool steels are better.

Everyone who has used one of these asks "How did you get it so sharp?"

We use the lathe, with a 6 inch wheel between centers, with the blade mounted on

a fixture on the tool post. We set the traverse very slow, it takes about 10 minutes

per pass down the blade, about 4 passes per side, and results in a very nice hollow

ground edge. For final sharpening after hardening, we use one of those little

angled carbide things you can get at the hardware store.

Sometimes the cheap stuff really works.

Woods we use. All grown here.

| Oak |

Oak comes in many flavors, red, white, pin, live and others. Each has a

unique look. It is very strong, and an ideal knife handle material. We of course

select for beauty, rather than what the flooring guys do. We go out of our way

to find crotch pieces, knotty pieces and suchlike, which finish up very nicely. |

| Walnut |

The traditional favorite for gunstocks, it makes nice knife stocks as well.

Some samples have truly beautiful grain and ray patterns. Not as hard as oak,

but hard enough for most people's uses. |

| Cedar |

Cedar can be utterly beautiful, as we found out when we put a small but

old cedar tree out of its misery after a truck ran over it. All those tiny branches

make for a nifty figure, and if the tree has grown up a little warped, the resulting

grain patterns are out of this world. Just one problem. It's really too soft for a

"working" knife. We like it anyway, and some people are really careful.

|

| Wild Cherry |

Sometimes bland, but can be gorgeous if you get the right chunk of it.

This is the hardest wood we work with, at least in what grows around here.

This raises costs somewhat, as it is hard on the tools as well as the knifemaker!

|

We will also work with whatever you send, or use any metal we can get, which

is most of them. Some people seem to like handle-heavy knives, and making the

handle out of brass or aluminum will get you there. Either can be hollowed out,

of course, to make them a little lighter and perhaps provide a little compartment

for things.

Here is as close as we get to a non–custom knife.

I found this nice piece of Cedar, and just went ahead and made a blade for

it. Once someone comes along to love it, I will then adapt the stock to

fit them. For now, it looks nice hanging around the shop as an example

of what can be done. This picture doesn't do it justice, as the wood

figure is sort of 3–D and everything moves when the light does. It

will take better lighting and a movie to really show how nice this

thing looks.

Here is as close as we get to a non–custom knife.

I found this nice piece of Cedar, and just went ahead and made a blade for

it. Once someone comes along to love it, I will then adapt the stock to

fit them. For now, it looks nice hanging around the shop as an example

of what can be done. This picture doesn't do it justice, as the wood

figure is sort of 3–D and everything moves when the light does. It

will take better lighting and a movie to really show how nice this

thing looks.

|

Here is a knife someone brought to us to restore. This picture was taken

in the middle of the process. When we first got it, it wasn't very recognizable

as a blade. Careful use of mechanical and chemical means got

it to this point.

Some of the metal inlay is missing, and will be replaced. The customer said

his grandfather got this somewhere in South America. The decorations are

obviously Islamic. When cleaning out the hand stamping on the blade,

what came out was garnet powder, so this may have been used near a mine.

The stampings on the blade have some further engraving or stamping down in the

bottoms, the pattern is quite complex.

The stock is ivory, the metal inlays are pewter, the blade is hand forged

high carbon steel, and takes an excellent edge. We would love to hear from

anyone who might be able to fill us in on the possible history of this item.

It was obviously made in a time when skilled hand labor was inexpensive.

Here is a knife someone brought to us to restore. This picture was taken

in the middle of the process. When we first got it, it wasn't very recognizable

as a blade. Careful use of mechanical and chemical means got

it to this point.

Some of the metal inlay is missing, and will be replaced. The customer said

his grandfather got this somewhere in South America. The decorations are

obviously Islamic. When cleaning out the hand stamping on the blade,

what came out was garnet powder, so this may have been used near a mine.

The stampings on the blade have some further engraving or stamping down in the

bottoms, the pattern is quite complex.

The stock is ivory, the metal inlays are pewter, the blade is hand forged

high carbon steel, and takes an excellent edge. We would love to hear from

anyone who might be able to fill us in on the possible history of this item.

It was obviously made in a time when skilled hand labor was inexpensive.

|

Coulter's Smithing Home

Here's how to contact us:

Contact information

We make custom knives here, sort of as a hobby, but it has turned out to

be a profitable one. We are not as good at it as some of the masters,

like, for example

this guy, or

this guy,

but so far we are not getting any complaints either. Unlike some

of the pros who are not really custom, but make batches and then

sell them, we actually make each knife for each customer, to a design

the customer helps with or likes -- this sometimes results in unusual

designs, which is fine with us – and more fun sometimes. We fit

each to the customer's hand,

something impossible to do in batches. We also pick the steel type

based on the customer's desires, uses, and skills with knife type tools.

We make custom knives here, sort of as a hobby, but it has turned out to

be a profitable one. We are not as good at it as some of the masters,

like, for example

this guy, or

this guy,

but so far we are not getting any complaints either. Unlike some

of the pros who are not really custom, but make batches and then

sell them, we actually make each knife for each customer, to a design

the customer helps with or likes -- this sometimes results in unusual

designs, which is fine with us – and more fun sometimes. We fit

each to the customer's hand,

something impossible to do in batches. We also pick the steel type

based on the customer's desires, uses, and skills with knife type tools.

Here is as close as we get to a non–custom knife.

I found this nice piece of Cedar, and just went ahead and made a blade for

it. Once someone comes along to love it, I will then adapt the stock to

fit them. For now, it looks nice hanging around the shop as an example

of what can be done. This picture doesn't do it justice, as the wood

figure is sort of 3–D and everything moves when the light does. It

will take better lighting and a movie to really show how nice this

thing looks.

Here is as close as we get to a non–custom knife.

I found this nice piece of Cedar, and just went ahead and made a blade for

it. Once someone comes along to love it, I will then adapt the stock to

fit them. For now, it looks nice hanging around the shop as an example

of what can be done. This picture doesn't do it justice, as the wood

figure is sort of 3–D and everything moves when the light does. It

will take better lighting and a movie to really show how nice this

thing looks.

Here is a knife someone brought to us to restore. This picture was taken

in the middle of the process. When we first got it, it wasn't very recognizable

as a blade. Careful use of mechanical and chemical means got

it to this point.

Some of the metal inlay is missing, and will be replaced. The customer said

his grandfather got this somewhere in South America. The decorations are

obviously Islamic. When cleaning out the hand stamping on the blade,

what came out was garnet powder, so this may have been used near a mine.

The stampings on the blade have some further engraving or stamping down in the

bottoms, the pattern is quite complex.

The stock is ivory, the metal inlays are pewter, the blade is hand forged

high carbon steel, and takes an excellent edge. We would love to hear from

anyone who might be able to fill us in on the possible history of this item.

It was obviously made in a time when skilled hand labor was inexpensive.

Here is a knife someone brought to us to restore. This picture was taken

in the middle of the process. When we first got it, it wasn't very recognizable

as a blade. Careful use of mechanical and chemical means got

it to this point.

Some of the metal inlay is missing, and will be replaced. The customer said

his grandfather got this somewhere in South America. The decorations are

obviously Islamic. When cleaning out the hand stamping on the blade,

what came out was garnet powder, so this may have been used near a mine.

The stampings on the blade have some further engraving or stamping down in the

bottoms, the pattern is quite complex.

The stock is ivory, the metal inlays are pewter, the blade is hand forged

high carbon steel, and takes an excellent edge. We would love to hear from

anyone who might be able to fill us in on the possible history of this item.

It was obviously made in a time when skilled hand labor was inexpensive.